Lieutenant Norman Leslie had been on watch for several hours when he spotted the track of a torpedo heading straight for the ship. Despite the obvious danger, he noted it was running on the surface, a brilliant red in colour with a black head. As the HM armed boarding steamer, Duke of Albany’s second-in-command, he immediately gave the order, “hard a starboard”, rang up the engines for “full speed ahead”, while sounding the gongs to alert the general quarters. The torpedo from the German submarine, UB 27, struck the ship a little off its centre, just after 9am. Two men were killed instantly. A black column flew into the air, one lifeboat with it, when Lt Leslie noticed a second torpedo, heading their way. It passed about 20 to 30 yards astern.

The ship sank within about five to six minutes. She had set off from Longhope on patrolling duties with the Duke of Clarence on the morning of August 24, 1916. The official report summed up the sinking: “At 9am, the ships being in line abreast, about one-and-a-half miles apart and the Duke of Albany to the northward, proceeding at about 14.5 knots and zigzagging on a true east course, a torpedo was seen at about 300 yards distance, running near the surface. “The officer of the watch, Lieutenant Norman Leslie, Royal Naval Reserve, at once out the engine room telegraph to full speed and the helm hard a starboard to avoid the torpedo, which, however, struck the ship under the port engine room a few feet only below the water line at 9.03am.” The emergency bells were rung and the hands were at their action stations by the time the explosion took place. A few seconds later a second torpedo passed close astern running deep.

The ship started to settle at once, slightly by the stern, and six minutes later she turned bows up and sank quickly stern first. Tragically, there was not sufficient time to replace the catches of the depth charges and their exploding accounted for many more casualties. It was recommended thereafter that all ships who keep the catches out should specially arrange for a man to replace them if the ship is badly damaged. It was also noted that the ships confidential books were placed in their steel chest and thrown overboard despite the very limited time available — this was largely due to Lt Leslie.

Credit was also paid to the officer for going down below when the ship was sinking to bring up a sick patient who was under his charge. As one of the survivors, Lt Leslie gave evidence at a court of inquiry. He said: “The captain ran up on the bridge as soon as the gongs sounded. I left him in charge of the bridge and went round to see the damage.” Shortly after, the captain, Commander George Ramage, ordered them to abandon ship. Lt Leslie continued: “I then suddenly remembered that I had a patient, one of the officers being ill. I rushed down to his room and felt in his bunk but he was away. I then slipped out by another door opening on to the saloon deck and found my boat level with the rails and jumped in.” The captain perished. He told how it was impossible to get their lifeboat away from the side of the ship, which was sinking quickly. “Then the after davit fouled the boat and capsized it bearing us down. We were underneath the boat for about five minutes. “I saw two of our boats fully loaded and all around there were rafts and men hanging on to them. The Duke of Clarence came along and lowered two boats. I then steered through the wreckage with her boats three times picking up survivors.” One hundred and six men were on board, and 25 died. “We had practised abandon ship 24 hours previously when in harbour,” Lt Leslie said. “Everybody actually going away in the boats.” Asked how he accounted for the loss of lives, the lieutenant replied: “The ship sinking so rapidly and their being dragged down, the capsizing of certain boats and the explosion of the depth charge after the ship sank.”

Chief petty officer, John Davis, of the Royal Fleet Reserve, was also called upon to give evidence. “At abandon ship I went to my boat which was one of the cutters but found that it could not be worked as the davits were jammed. “I then sent my men to go in the gig. I lowered the foremost fall and when it was in the water the after fall was cast off. I told them to hang on to the lifelines and cast off the foremost fall but before they could do so the gig swung broadside on and capsized owing to the ship still having way on.” Asked if there was any confusion, the petty officer responded: “I never saw anything quieter in my life.” After the gig capsized, CPO Davis went aft to try and put a safety catch in the mine to prevent an explosion when the ship submerged. He found he was too late as the mine was already in the water when he got there. “I swan away from the ship. I do not think the mine was more than 20ft under water when it exploded.”

The Duke of Clarence at once proceeded, full speed, towards the Albany, slipping two boats close to the men that were swimming and endeavoured to ram the submarine, the position of which was indicated by a swirl on the surface of the water. The acting lieutenant on board the Duke of Clarence, David Alexander Jack, was the navigating officer when the Albany sank. He made for the deck when he saw smoke and steam coming from the nearby ship. “At 9.20am we stopped for just long enough to drop two boats. Then going ahead again at full speed circling round and zigzagging. We saw what looked like water being pushed aside — like shallow water going over a shoal — about half a mile ahead. “We let off a shot at it which fell short and ricocheted over it. We then went straight for it and passed right over it, but felt nothing on the bridge.” The captain of the Clarence and Lt Norman Leslie were both recommended for commendations for their bravery. The recommendation reads: “It is submitted that Lieutenant Norman Leslie, of HMS Duke of Albany is deserving of their Lordship’s commendation, also Lieutenant-commander Cecil Burleigh, commanding HMS Duke of Clarence, who stood by his consort at considerable risk and saved 17 lives in his ship’s boats, keeping the submarine off until the arrival of the torpedo boat destroyers.”

The loss of the Duke of Albany would also prove to be a pivotal point in naval history. The court of inquiry found: “When any vessel is in imminent danger of sinking all depth charges should be rendered inoperative by inserting the safety catch, so as to prevent loss of life (and further damage to a vessel which might subsequently be salved) due to the depth charges exploding after the vessel has sunk.” The tragic loss of the lives on board the Albany almost certainly helped save others in the years to come. The Court of Inquiry also considered whether the watertight doors of the remaining armed boarding steamers can be kept closed at sea. The report states: “Should the reports from the other vessels, called for by the commander-in-chief, show that the watertight doors, or at least those bouding the main compartments, cann be kept closed when at sea, there will be much greater chance of the damaged vessel remaing afloat, or at any rate, of sinking less rapidly then in the present case. “In these small vessel where there generally is, or can be made, direct means of access from each main cmpartment to the uppoer deck, it is a matter for consideration whether such doors should not be permamently closed. Three of those who perished duirng the sinking of the ship are buried in the Lyness Naval Cemetery — petty officer Charles Henry Couch, of Devonport, aged 51; fireman Edward Phillips and Edward Smith, greaser.

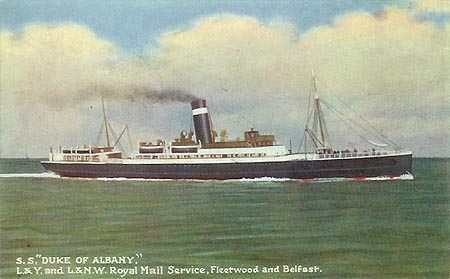

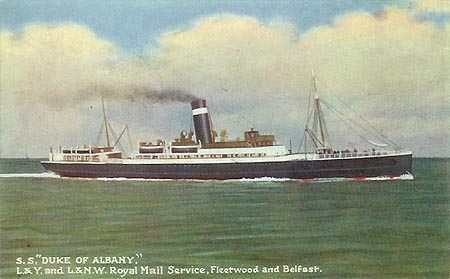

A First World War armed boarding steamer — whose sinking changed the course of naval history — has been discovered off Orkney. Most of the 25 men who perished after the HM Duke of Albany was torpedoed by a German U-boat in August, 1916, died as the ship’s own depth charges exploded as she sank. An inquiry later ruled that all depth charges must be made safe if a vessel is at risk of sinking — a ruling which almost certainly saved many lives of those at sea. The exact location of the wreck is a closely guarded secret, by Stromness researcher, Kevin Heath, who has been successful in identifying the resting places of several other ships and submarines in Orkney waters. He said the identification of the wreck had been confirmed by a team of divers, who found and raised the ship’s bell on Tuesday of last week, with one describing it as the “pinnacle of any diver’s career”. “I had been interested in this wreck for a while and I decided to try and find it. It was not in its charted position, but about five miles away,” Kevin said. As to how he tracked it down, Kevin added: “From the Court of Inquiry from the U-boat log and from chatting to fishermen. This is the first time this wreck has been dived; nobody knew where it was.” Kevin is thrilled at the team effort, which he says would not have been possible without the divers, Barry White, Leigh Grubb, and Paul Bell, and Andy Cuthbertson of Scapa Flow Charters. The Receiver of Wrecks will be notified of their discovery and a decision will be made as to where the bell should be displayed. “This may provide some closure for the relatives of those who died,” Kevin added. Forty-one-year-old, Leigh Grubb, from north Wales, said it was always a privilege to dive a virgin wreck. After descending to the sea bed at nearly 78 metres, she said they were right upon the wreck. “Andy was spot on with the shot line which had landed beside a collapsed staircase. Paul and I swam towards the stern. It has a slight list to starboard. The back of the boat is fairly blown up; it was probably the depth charges that did that. “We saw the area where the torpedo had hit and then the two propellers, some of the blades had been sheared off. Then we swam back over some of the mangled wreckage.” Then Paul summoned Leigh to come over to where he was. “It couldn’t really be the ship’s bell, with the ringer still inside it, upside down and heavily concreted in? Our eyes adjusted as we came to rest next to it. It was. That was awesome as it is definitive proof. Finding the bell, well you don’t get any better than that. They are every diver’s dream.” Working together the divers managed to dislodge the bell and bring it very slowly back to the surface to show Kevin and Andy. Leigh added: “Getting back on the boat was highly entertaining, I crawled most of my way across the deck, it was too rough to walk. But then Kevin unclipped me from my unit and pulled me into a massive bear hug. It was an awesome moment. “Absolute, incontrovertible proof that this was the Duke of Albany. Stunning. All the years of hard work and research culminating in that one moment of absolute vindication. I am totally humbled, and I know the others are, to have been privileged enough to be allowed to be a small part of that triumph.” Leigh described it as a poignant and atmospheric dive. “Twenty-five men died on the Duke of Albany, two of them when the torpedo hit. The others died as it was carrying depth charges that went off. All depth charges had to be made safe after that if a ship was going to sink.” Leigh has the bell with her at home in north Wales and is planning on cleaning it before returning with it to Orkney. The 100-metre Duke of Albany was built by Brown and Co, Glasgow, in 1907, and had been a renowned steam ship working from Fleetwood to Belfast. She was taken over by the British Admiralty in 1915 for service as an armed boarding vessel. Several years prior to that the vessel had earned her place in history transporting the Titanic’s centre anchor, weighing 15 and a half tons, from Fleetwood across the Irish Sea to the Harland and Wolff Belfast yard.